FILM REVIEW: Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

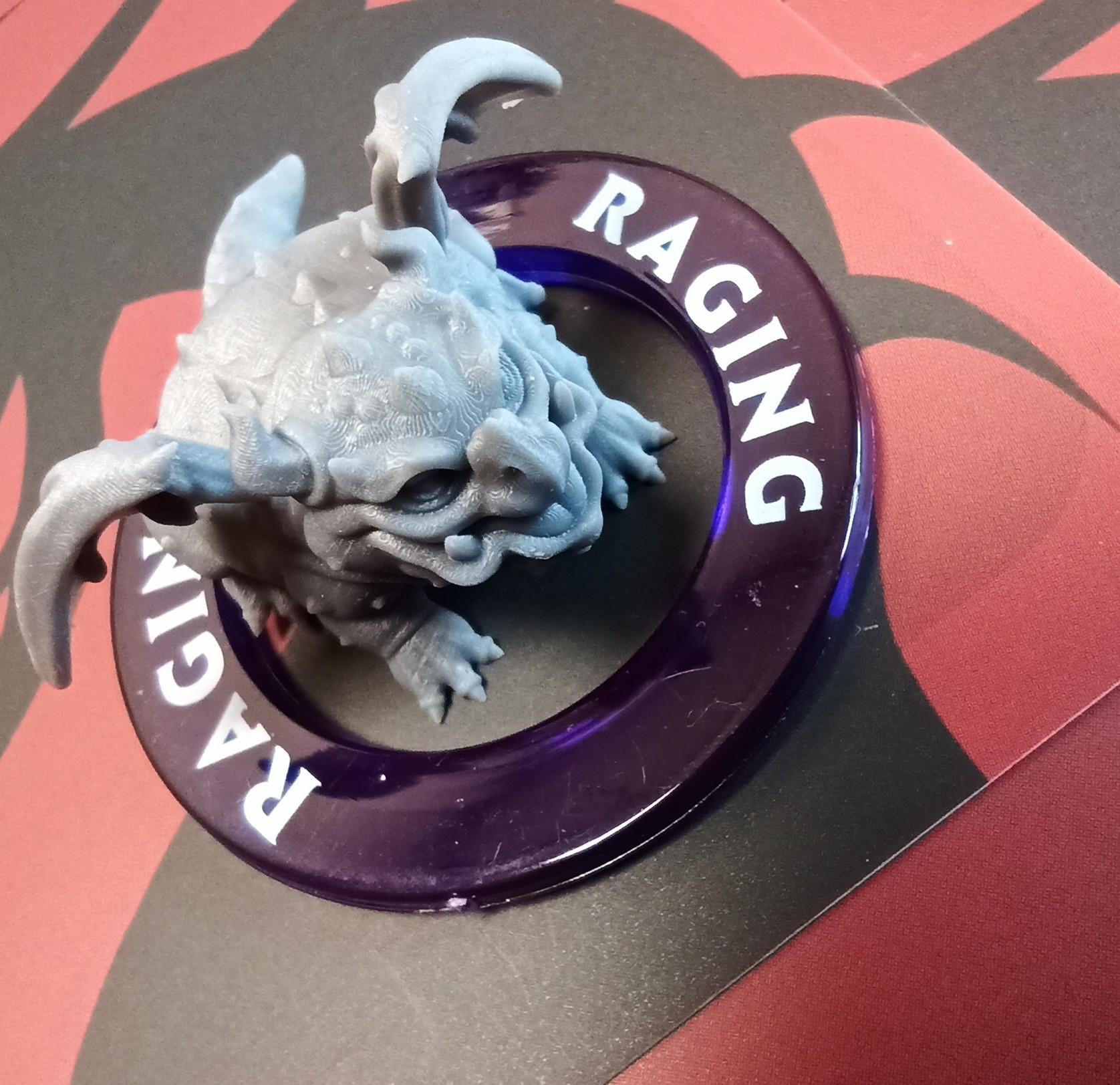

[PHOTO: An angry little fat dragon, today.]

Contents

Honor Among Thieves is post-woke

Intro

[My first proper Substack post was going to be my reflection on a blog rant about Labour-Party “moderates” that I wrote in November 2016 and never published, but I wanted to start on a positive note, so have a cosy, complimentary film review instead.

And I came to this site in the first place as a geek-for-hire, who accidentally started a Substack while exploring the medium from a technical point-of-view. What better way to do that than to write about an extremely geeky multimedia franchise?

I don’t want to launch by getting cancelled and I want to test all the features of this platform. This is perfect in both respects.

Is my being nice about cult culture boring? You’ll get my political rants soon enough.

Does this article go on too long and say nothing controversial? I wanted to write beyond the size limit of the email format to see what happens, and, if you have no interest in Dungeons & Dragons or have read plenty of similar reviews of the film and you just want A Bit Of Politics, then you can jump straight to “Honor Among Thieves is Post-Woke”.]

[Photo: As with the habit of smoking, the shiny, tactile paraphernalia of Dungeons & Dragons is almost as addictive as the game itself. This addiction is perhaps one reason why, during its 1990s relative decline, it lost out in popularity with on-the-spectrum males to fantasy wargaming, in which there are so many more bizarre figurines to paint. That role-playing came to dominate the way fans played D&D is ironic, because the game’s creators designed the game for combat.]

Here’s my original Twitter thread about this film:

Revenge Of The Nerds

Like a lot of people since the Netflix debut of 1980s kids’ nostalgia/SF/horror series Stranger Things in 2016, I’ve recently begun to re-explore my childhood interest in the sword-and-sorcery role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, the game that allowed schoolboy nerds like me—and of course the geeky characters of Stranger Things—to take on heroic fantasy personas and thereby pretend to be strong, sexy, and dangerous.

And “dangerous” even in the real world, where D&D was, at the time in which Stranger Things is set, widely believed to be a gateway to Satanism—as if the Evil One would be interested in recruiting spotty teen virgins with lollipop-stick biceps to his armies of the dead. Though, to be fair, quite a lot of us were good enough at chemistry to manufacture explosives.

As the game itself has grown and developed from its messy, paper-based, Tolkien-bothering origins into its slick, very-online 5th-Edition form, in a 21st century when geeks are tycoons and sex symbols, there have been plenty of attempts to turn its increasingly valuable cult intellectual property into mainstream multimedia #content. Finally, it looks like the current rights owners, US toy giants Hasbro, have found a chest of gold. As often when this happens, they’ve also accidentally made Art1.

The Movie

There are a lot of mainstream media reviews of Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves saying a lot of the same things about it, so I’ll get those obvious points out of the way first, then try to say something different about it.

It’s good

Audiences love it. I’m such an anti-elitist about cinema that I am more inclined to put my faith in the great unwashed than soapy dwellers in the media bubble, but you can see from Rotten Tomatoes that critics love it too.

It’s well-written

Like The Wizard Of Oz, no matter how complicated the fairytale gets, the questing protagonists’ motivations are clear. So the story is solid. But, even close up, at the fine resolution of dialogue, the stitching is meticulous.

It’s Pythonesque

A highlight of the script’s needlework is its comedy. Everyone wants to praise the production for “not taking itself too seriously” (perhaps because it’s important to many critics that genre movies shouldn’t be taken too seriously). Obviously, in our post-MCU world, there is Avengers-style banter between the leads, but the plot is just as self-aware.

One example: “Sword-and-sorcery is about quests,” the writers seem to have said to themselves, “But, instead of subverting the trope, let’s double down on it! Let’s go quest crazy! Then, let’s render some of the quests pointless!”

But, within that plot, no one breaks the fourth wall and none of the players out-and-out mugs it up for the cameras; the film is funny because the script is funny, and because the actors delivering the script give themselves completely to it.

And, as this clip shows, it’s Monty-Python funny because, like Python, it takes the arbitrary and absurd rules of the game/philosophy/history seriously and explores the consequences to their conclusion. Believe it or not, not only does this sequence extend to the exhumation of most of the bodies in this war grave, but this joke, which is set up about a third of the way in, continues to the post-credits sequence2.

It’s well-cast

Seldom3 since his turns as Captain Kirk has Chris Pine so transcended his status as an interchangeable Hollywood Chris and delivered a performance distinctive in itself and so fitted to the task in hand. Pine is a bard called Edgin. Among warriors and wizards and witches and the wise, the best he has to offer is charm. In a charm offensive, it’s perfect that his evil antagonist should be played by Hugh Grant, a fake lord called Forge.

Michelle Rodriguez, whose movie debut was as a female boxer, takes the implausible trope of the kickass shortarse girl and, with her build and movement, and by force-of-personality, makes you believe it. But she isn’t just on board as the muscle. She might not be the official protagonist, but her character’s trajectory is the most interesting and, ultimately, the most important. And her love life delivers more Pythonesque visual gags.

The other cast members are just as nicely chosen and, to my personal delight, at least four of them are mixed-race actors. About which more later.

It’s a technical tour-de-force

I have tweeted about this already,

but, beyond the clever trippiness of perspective, there’s also a dedication to giving the fairytale surface sheen of the film’s cinematography—almost cartoonish near-Technicolor at times—some texture and heft. Partly this is down to the choreography of the action sequences, but real craft has been (sometimes literally) poured into the details.

“Every single time we had something physical generated from a character’s hands, we thought, what is the physical metaphor here?” [Compositing Supervisor at ILM] [Todd] Vaziri recalls. “If they’re generating a fireball, we need to make it feel like there was a fireball on set. If another spell is, say, affecting water to generate a giant wave, well, when somebody’s moving their hands around, what comes off of them? How about super fine mist? Maybe you’ll see droplets…maybe you’ll see that it’s emanating from their hands. We wanted to make it feel like the actors had something in front of them. That’s where we want to be.”

It’s true to the game, but not a slave to it

Of course the film takes place in an established realm of the D&D game world, of course it references real species and characters and social structures, and of course it follows the format of an actual game campaign; but there’s more to its authenticity than that. ([SPOILERS!] And it doesn’t stick to the rules anyway.)

Things go to shit in the game because it’s inherently open-ended, human-player-driven, and non-linear. When he prepares an adventure for them, the game-runner cannot possibly know what the game players will do at each turn, so he and they have to improvise when matters don’t go according to either’s plan. And they are very often fixed with creativity. This is one of the many reasons why real D&D is fun. Without spoilery, I have only two words to say about how the on-screen version cleaves to this chaotic goodness: “portal sequence”.

Honor Among Thieves is post-woke

I don’t think it’s an accident that, in a pseudo-historical world that contemporary Hollywood could have remade to feature Cool-Kid social-justice agitprop, this production chose instead to focus on themes of “found family” and good old-fashioned spectacle, especially when the game it’s based on has long been a fantastical refuge for social outcasts wanting to join a gang, away from those Cool Kids. And I don’t think it’s an accident that that choice was rewarded with commercial success.

But the film doesn’t grind any axes for more-unfashionable philosophical positions either—like, say, The Incredibles did. It’s a themed rollercoaster on rails. You get on; you enjoy the ride; and at no point does anyone hand you a campaign flyer. So I’m not calling it anti-woke; I’m calling it post-woke.

Want to do a gigantic, extended fat joke without being accused of fat-shaming? Have a fat non-speaking dragon! BONUS FOR THE FANS: The fat dragon in question is actually canon.

Once They Were Wokerer

As I explain in the final section of this article, the essentials of Dungeons & Dragons are free to play, thanks to its very open licence and generous distribution of the core of the intellectual property. This choice has not only helped interest in the game to spread widely, but spawned a vast commercial ecosystem of third-party games and co-branded commercial partners.

But Kyle Brink, Executive Producer of D&D-the-game had to apologise twice because of a user backlash against trying to change that licence in (at least) two ways:

by insisting on greater control of derivative works, and

by trying to punish users for their politics—anyone using the licence could have it terminated if they produce related content that was:

“blatantly racist, sexist, homophobic, trans-phobic, bigoted or otherwise discriminatory”

You can read more about the licence controversy here, but the obvious point I want to make, and another reason why I chose “post-woke”, is that the property-holders have had their fingers burnt once. They seem to have learned from this experience.

Café-au-lait society

The cod-mediaeval world of D&D undocks the film from any requirement of historical accuracy: the actors can be any colour—in Honor Among Thieves, several of them are more than one colour at the same time—but no one is beating us over our heads with a morning star about this. It simply isn’t a biggie.

And this is made all the less of a big deal by giving major roles to members of the Mixed-Race Massive like Regé-Jean Page and Justice Smith (whose English accent is so convincing throughout I had no idea he was Californian until I looked up his name). You don’t have to worry about diversity auditors asking “How many of the leads are black and how many of the leads are white?” if the answer is “Yes.”

And it’s not just the good guys who are beige. A half-Indian actor [of my own acquaintance!] plays one of the worst people in the film.

Against tribalism

But the world of D&D the game is a world of races—not “races” as in “black, white, and yellow”, but “races” as in Elf and Kobold—and clans. The film can’t avoid this. It doesn’t. One recurring themes is the way in which Edgin’s (and others’) prejudice against certain species/alliances/guilds gets in the way of The Quest, and a particular arc rests on the question of whether or not he was wronged by one order (of peacekeepers) in particular.

The wokest of all the subplots concerns the “mixed-race”—in the sense of “D&D race”—character among the principals, who is rejected from birth by her human parents. The wokeness is less to do with this, but with an ecological threat to the Wood Elves she chose for family. But, just like Pine’s character, she has to learn to trust those she feels betrayed her.

Even the standard Disneyesque message that one should Believe In Yourself, embodied by another member of the adventuring party, is subverted, in the most explicit example in the story, by challenging the idea that one’s calling is inherited, rather than a function of practice and perseverance.

Biological sex doesn’t matter

Long before the trans wars, D&D was a medium through which adolescents could take on whatever sex or orientation they wanted, and the rules of the game encouraged it—yet another way Honor Among Thieves is true to their spirit. No one in this story treats biological sex as any kind of issue. People do what they do, and no one needs to change sex or gender to do it.

Some of its best jokes are about the domestic arrangements of the main characters, but they work independently of sex stereotypes. It’s as if the writers side-eyed the carnage in Harry Potter fandom and made a conscious choice to side-step it.

A message of family and fate, not social justice

I’m not going to spoil anything by describing the climactic moral choice in anything but the most abstract terms. But it’s a choice that has nothing to do with class or colour or climate change. It’s one about karma and kin.

Is this the future?

Given its commercial and artistic success so far, it looks likely that there will be a sequel, so, in the most cynical sense: Yes. Though, like all the best franchise films, it was written without a sequel in mind.

In the political sense, post-woke—rather than either woke or anti-woke—film-making seems to have had a good run recently. If you build a big, bold, fantastical franchise, and put aside ideology, audiences will come.

Of course, there’ll always be party poopers, griping for clicks; of course The Guardian’s loftily dissenting review called the film “passable” (three stars out of five); but it’s beginning to look like the way for art to win over politics is to ignore the ideologues and entertain your audience.

But what about the game?

Why you shouldn’t play D&D

I like Dungeons & Dragons, but it’s not for everyone. There are good reasons why it has always appealed to nerds over normies:

If you play the real thing, it’s complicated.

Even if you’re up for the complexity, to have a feel for what’s going on, it helps to have read some classic fantasy and pre-modern history—or at least to have watched a lot of genre films.

You can play it for free, but it’s better if you invest in a few props to keep track of things. (You don’t need to invest money; you can invest time instead.)

If you’re into pure competition—winning and losing, crushing your enemies, seeing them driven before you, and hearing the lamentations of their women—standard D&D will disappoint you. It’s a role-playing game. If you want to be pretentious, it’s more like collaborative theatre than virtual combat.

It’s the opposite of a videogame: The action takes place at a steady pace in your mind’s eye and not at a noisy 60fps up on a screen. If you have adapted to that level of intense, real-time stimulation in your gameplaying, look elsewhere.

Dungeons & Dragons is absurd. I don’t mention this strictly as a reason not to play the game. But it is something that is fundamental to the question of whether you, personally, would enjoy playing it. For a game of D&D to succeed, you have to, like the cast of this movie, embrace the absurdity and commit to the story. You have to be willing to do things that look silly to outsiders, but doing such things willingly is central to the fun.

Why you should play D&D

But, if you are still a child at heart (perhaps a drama-club child who was never cool enough to be invited there4), enjoy sword-and-sorcery worlds, don’t mind doing some homework, have a handful of friends and/or children on a similar wavelength, a bit of time to spare, and a big table and chairs, then jump in! The worst that could happen is you’ll waste twenty quid and a free afternoon.

D&D is going cheap at Amazon

If you want to play Dungeons & Dragons, you don’t need to buy the full official core rulebooks. Everything you need is online, legally, for free. But, a few weeks back, I pointed out that the full official core rulebooks are available discounted from around £140 to about £86.

Possibly because of the film, they are now even cheaper: at a less weird-sounding price point of £79.99.

But what I would recommend instead, is either this, if you are a beginner yourself and you are introducing kids to the game:

Because, while it contains many elements of D&D proper, it’s much more like a conventional board game, so should ease the transition.

Or, if you are familiar perhaps with earlier versions of real D&D and want to get back into the game with people who are or are not previous players, try this:

Because it’s also cheap right now (£14.99), contains all the basic rules you need to play, a bunch of characters you can pretend to be, an adventure for you all to follow, and a set of dice. There are also lots of videos and other resources online that explain this adventure and can help you refine it and enhance it—including that play-it-on-the-cheap video I linked to earlier.

All of these options do, however, require that you have some friends or willing relatives to play the game with, and one of you has to be the storyteller/referee: The Dungeon Master. I’m not sure that it’s a weakness or a strength of Dungeons & Dragons as a game for nerds that you can’t play it if you’re a nerdy no-mates—unless you go outside and find some mates.

—not Elite Art, but definitely Popular Art.

Actually mid-credits sequence.

I strongly recommend Hell Or High Water as a Pine at his finest..

I’m not bitter.

Recent Comments