I often grumble here that there’s no such thing as “timeless greatness” in art. Everything from subject matter to structure to execution to meaning depends on the circumstances that prevailed when a work was made. Indeed, if a work is published into another set of circumstances, it can escape its creator’s intentions completely, even without significant time having passed since it was first enjoyed. A piece that started as a private contemplation can mutate into a commentary on a catastrophic event that was unknown during its completion but that dominated the world of its release.

Today, I noticed two not-new commentaries on the way in which the format of music, the way a listener experiences it, defines both the way composers and musicians make music and the way audiences think of it after it has been made.

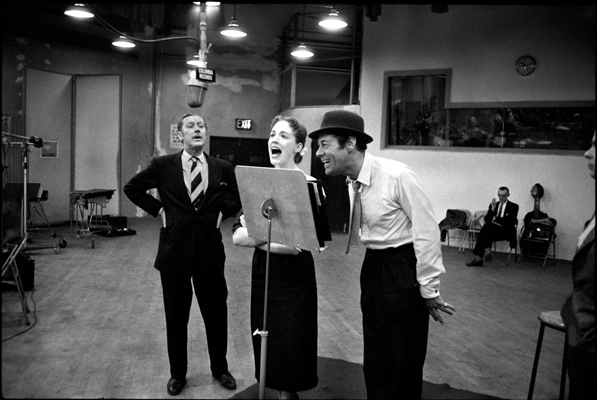

The first was The Birth Of 33⅓, a (too short) extract of the upcoming book 360 Sound: The Columbia Records Story in Slate magazine, illustrated with (too small) photos of people like Frank Sinatra, Miles Davis, and Aretha Franklin looking impossibly cool in recording studios.

You can read it like you would watch an episode of Mad Men, raising one of your eyebrows aloft using only the power of hindsight:

No less interested than Columbia in finding a solution to the problems in playing long-form musical pieces on 78s, RCA had developed a rapid record changer, which would allow listeners to stack a large number of records around oversized spindles above the turntable. The records, which played at 45 rpm, would then quickly and automatically drop to the turntable in ordered succession, creating a virtually uninterrupted flow of music. The goal was the same as that of CBS’s microgroove LP; RCA simply pursued it with a different technology. Now, rather than switch to Columbia’s long-play technology, RCA would fight.

The second was this recording of a design/architecture radio show from earlier this year, in turn quoting a brilliant snippet from recording of a talk by composer Jon Brion. In it, amongst other things, Brion explains why covers of Led Zeppelin are unsatisfying. He tries to impress upon his audience the important distinction between a song and a performance, he does this well: by performing snippets of songs.

If you are normally afraid of podcasts because the lack the concision and searchability of all the other stuff you graze on on the Net, then don’t be; if you’re a music geek, every second of this one is worth savouring—up until the show’s outro, obviously:

Recent Comments